Critical Theory is a play on semantics. The theory was simple: criticize every pillar of Western culture—family, democracy, common law, freedom of speech, and others. The hope was that these pillars would crumble under the pressure (Zero Hedge, ‘The Birth of Cultural Marxism’).

Through all of human history societies have protected children. When a society stops looking after its young, it has reached a level of degradation from which recovery could well be impossible.

The campaign to ‘protect the sexual rights of children’, ie to eroticise them from a young age, is bedded in the cultural-Marxist strategy of undermining the family (aka Critical Theory) by making it hard for people to form permanent relationships. While the stated intention of Critical Theory was to undermine the institutions which stood in the way of the adoption of Communism, early sexualisation and of course transgenderisation also serve the purposes of the associated eugenicist movement.

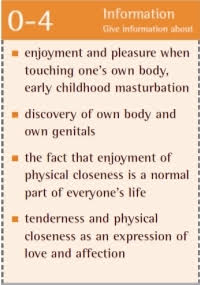

Education departments throughout the Western world are incorporating programmes to further the Marxist goal of sexualising the young. The World Health Organisation recommends instruction in masturbation for European toddlers from birth to four years of age. Importantly, an association is created between tenderness, physical closeness and sexuality.

Eroticisation of pre-schoolers may not yet be applied in New Zealand, but it cannot be far away, particularly under a hard-line Marxist administration. The teachers’ resource for the New Zealand sex education curriculum, Navigating the Journey: Sexuality Education: Te Takahi i te Ara: Whakaakoranga Hōkakatanga (overview here):

- Recommends the sexualisation of children from the age of five

- Forces small children to question their gender identity

- Reinforces and exaggerates male-female stereotypes, and

- Presents a raft of ideas for undermining a child’s feelings of self confidence and self-worth which, while reinforcing the strong and successful, are threatening to the vulnerable.

Sexualisation of Young Children

(The volumes referred to here are for Years 1-2 and Years 3-4, principally, and Years 5-6, abbreviated to 1, 2, and 3. Thus 1/20 indicates Years 1-2, page 20.)

At present sexuality education in New Zealand begins at Year One, i.e. normally the age of five. The Guide to LGBTIQA+ Students: Plan Sexuality and Gender Education Years 1-8, which applies to all students (not just LGBTIQA), recommends:

‘Design learning programmes that meet students’ developmental

stages:‘Some children in this age group may be aware of the connection between

“making babies” and sexual pleasure.’

The actual teacher’s resource is more specific. As the sub-heading, ‘A blossoming takes place, a journey is set out on’, implies, it is intended that children are awoken sexually from the age of five.

From years one and two children are encouraged to talk to their families about ‘sexuality’: ‘what are some of the elements their whanau believe are important to growing up in all areas of our lives, including sexuality. (1/ p.10)

In the lesson on parts of the body (1/49), pupils are expected not just to learn, but publicly name, parts of the body including genitalia. This would normally be done in a mixed class – it goes without saying that any embarrassment a small child might feel in a discussion about private parts is heightened by the presence of the opposite sex. In some classes the number of boys versus girls is disproportionate – again this will increase the embarrassment or humiliation the minority sex will feel, whether male or female, and the likelihood of bullying.

Working in pairs, they are asked to write the names of body parts on labels and attach them after discussion to an enlarged body outline. They then cover the bodies with paper clothes and then hang them on the wall. Students can then lift the clothes to check on the accuracy of the placement – the purpose of the clothes is to prevent embarrassment apparently.

In years 3-4 (circa 7-8 years of age), pictures of naked people are presented to the children, who are taught and asked to identify what used to be called private parts, i.e. breast, testicles etc. They play ‘body bingo’. The teacher describes the sex act in detail, including sexual excitement (how the teacher should explain sexual excitement is not described).

‘Gender Fluidity’ and the Destruction of Identity

British figures to 2015 show that gender dysphoria amongst school children quadrupled in five years. Some argue that this reflects a widespread condition that has been hitherto suppressed, but it is impossible to overlook the part played by the active policies of educationalists in the English-speaking world.

The position of the New Zealand Ministry of Education is that transgenderism – which includes a gamut of options from gender self-identity to chemical puberty blocking to physical mutilation – is natural, common and to be encouraged. From the age of five or six, children are told that it is somehow natural for a boy to ‘identify’ as a girl and vice-versa. The conditioning starts in Years 1-2:

‘Encourage students to recognise that some people’s biological sex is different to their gender identity. For example somebody born with a penis may identity as a girl’ (1/49).

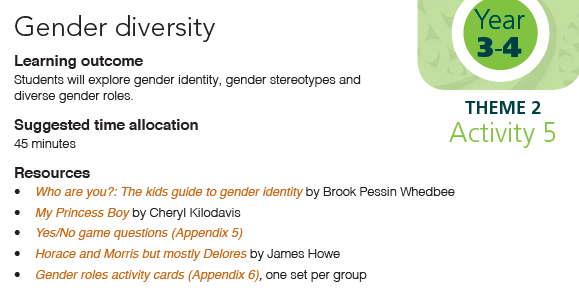

And is then reinforced in Years 3-4:

Encouraging gender dysphoria is a primary function of the curriculum for years 5-6, i.e. for children aged about 9 to 10. Of the four ‘themes’ in this resource, the subject is discussed in Themes 2, 3 and4: there are repeated calls to ‘affirm diversity’ and ‘affirm diverse genders’, and children are encouraged:

- to regard having a gender identity that does not match their biological sex as natural

- to envisage themselves having gender dysphoria.

‘Ask the students to use their imaginations and consider the following scenario:

Imagine waking up one morning and discovering that your gender has changed. What that would that be like? Allocate two questions per group for the students to discuss:

• How would your life be the same? How would it be different?

• Would any of your ambitions change?

• What could be some negatives about living with this “new” gender?

• What could be some positives about living with this “new” gender? [etc]‘ (3/30

‘What could be some negatives‘ is the closest to an acknowledgement that gender self-reassignment is the beginning of a road that leads to puberty blockers, sterility and ultimately mutilation, including castration for boys.

A 2008 study of the incidence of transsexualism among New Zealand passport holders gave a figure of ‘at least’ 1:6364. The ratio of male-to-female transsexual people to female-to-male transsexual people was 6:1: the prevalence of male-to-female transsexualism was estimated at 1:3639, and the corresponding figure for female-to-male transsexualism was 1:22 714.

There is no reason to believe that natural gender dysphoria amongst young children – a feeling that they are shut off from an identity they relate to – would normally even match this figure, particularly given the breaking down of stereotypes in modern life: girls can play almost all sports available to boys, boys learn to sew and cook, women travel the world on their own, and few careers are closed to either sex.

Reinforcing Gender Stereotypes

In order to facilitate gender dysphoria, there is a strategy to reinforce stereotypes, and then to make people who do not fit the stereotype feel threatened or different (1/p. 28). A correlation is created between choice of clothing, colours, hobbies etc and gender identity.

‘Where do messages come from about what boys and girls should wear and do we have to follow these messages. Encourage students to recognise that some people’s biological sex is different to their gender identity’ (1/50)

The purpose of the manual is sensitise children to gender stereotyping, ensuring that minority preferences within a gender are at the least a cause for self-consciousness.

‘Encourage the students to consider and question gender roles. Ask, for example, ”Who mows the lawn?” “Who does the cooking?” “Is this the same in all our families?” Gender roles can be different in different cultures and in different families. Avoid making

generalisations and encourage students to see diversity in gender roles.’ (1/41)

‘You could invite parents who live in non-traditional roles They could share how their gender does not affect their ability to do their job well.’ (1/29)

In years 3-4 students are asked to consider how they would behave in various situations: in the mall, at the beach etc (2/38). They are then asked to form groups of mixed gender, to consider the following questions:

- Do boys and girls make different choices to each other? Or similar choices?

- Do girls have to act in a certain way?

- Do boys have to act in a certain way?

And then (crunch question):

- What if you don’t feel like a boy or a girl?

In a group of 10 children, 5 of each sex, what if there is only one girl who likes climbing trees? How is she supposed to feel? And why does a threatening discussion on gender stereotyping have to lead to the even more threatening question of whether some boys should really be girls and vice-versa?

We have moved backwards from ‘girls can do anything’ to ‘if you don’t fit the stereotype, maybe you need a sex change’.

Undermining the Child’s Feelings of Self-worth

The more outrageous aspects of the programme – blatant sexualisation of children, forcing children to reevaluate their gender – are the tip of the iceberg. The recommended teaching style is intrusive, heavy-handed, patronising or preachy. The goal of the teaching programme is to invade children’s privacy, to make them expose themselves, and to feel competitive, uncomfortable, embarrassed, self-conscious, threatened, humiliated:

- ‘Ask students to brainstorm all the things that make them happy’ (1/41)

- ‘Ask the children how they are feeling today.’ (2/50) (It is not part of New Zealand culture to ask just anybody how they are feeling – a question which demands a certain level of intimacy. Otherwise, we ask, ‘how’s it going?’)

- ‘write down a goal to work on to contribute to family relationships’ (1/59)

- ‘ask the class to identify good listeners in the classroom’ (1/p. 16)

- ‘What do you like about your name?’ (Some children do not like their names) 1/(p. 18)

- ‘Explain that they are going to identify strengths in other members of the class. […] For example, “I think Marama is kind to other people because …”’ (1/p. 22)

- ‘Create a compliments kete and encourage your students to write notes to their classmates telling them what they do well […] and share with the class at the end of the week. If you notice that some students aren’t receiving compliments, you can write some for them to include in the kete.’ (1/p. 23). This serves to reinforce the well-established, popular, outgoing and successful at the expensive of the new, the shy, the less successful socially, academically and sporting-wise. (A good teacher would apply the alternative strategy of complimenting the more vulnerable members the class.)

- ‘How am I the same, how am I different? […] Why is it OK to be different’ […] Have the students describe what makes them different. What special quality, skill or interest do they have that is different from their classmates’ (1/p. 24-25)

- ‘Have students identify a part of their body that they like (2/66)

- Have the students draw ‘something they are really good at doing‘ (rather than something they like doing) (2/32)

- Children are asked to fill in a ‘pepeha’ template: ‘A pepeha is a way of introducing ourselves in Māori. A pepeha identifies who we are, where we’re

from, and where we belong’ (threatening to children who know they’re adopted) (1/p. 21)

Sex Education as a tool for teaching Maori language

The Sexuality Education programme has been designed to serve concurrently as a Maori language teaching resource. Children are frequently encouraged to use Maori instead of English, for example:

- ‘You could encourage your students to use te reo Māori as they talk about their whānau’ (1/20)

- ‘Encourage the use of te reo Māori vocabulary for feelings:

harikoa – happy

riri – angry

hōhā – annoyed [etc]’ (1/48) - ‘The students should be encouraged to pronounce the Māori names for body parts’ (1/49)

- ‘Students could practice te reo Māori phrases to describe how they are feeling’ (2/51)

Maori words and phrases are embedded throughout the text, and not always translated.

‘Discuss values and concepts for caring for others, such as wairua, whānau, hapū, iwi, whanaungatanga. Encourage the students to consider and share examples of these values and concepts from their own lives, for example, kaumātua caring for their whakapapa, hapū and iwi; sisters and brothers caring for each other, older siblings caring for younger siblings, parents, aunties, and uncles caring for children and so on. […]

‘Harakeke is unique to Aotearoa New Zealand and is one of our oldest plant species. Harakeke has important historical and contemporary uses. Many of the whakataukī and waiata associated with harakeke, such as “Tiakina te pā harakeke” and Hutia te rito o te harakeke, express values that are important to Māori.

‘Talk with your school whānau group, kuia, or kaumātua about their kaupapa (protocols) around gathering and using harakeke. Make links between taking care of the harakeke and taking care of people in our classroom, school, and families.e harakeke and taking care of people in our classroom, school, and families.’

According to the Guide for Principals, Boards of Trustees and Teachers:

‘The majority of Māori students attend English-medium schools. Research indicates that Māori students can thrive when “being Māori” is affirmed by the school, Māori culture is valued, and teachers are supported to challenge their attitudes, skills, and practices in relation to Māori students (Tuuta et al, 2004; Bishop et al, 2003). The revised guide aims to help schools to plan and deliver sexuality education and affirm the strengths and contributions of Māori students, whānau Māori, and Māori communities. The guide also recognises the diverse needs and strengths of students from Pākehā, Pasifika, Asian, and other communities within New Zealand.’

There are a number of issues associated with this policy:

- Major questions of curriculum should not be taken lightly – who decided on this strategy?

- In a case of mandated teaching οf Maori, is this the most effective, most empowering way to teach a second language?

- A number of New Zealand school children have English as a second language – should they be forced to learn another language, especially in this inefficient manner?

- Do Maori children want their language to be forever associated with the names for genitalia? Is this another device to expose children to humiliation and bullying?

- Is giving special emphasis to the ‘strengths and contributions’ of one minority culture at the expense of other minority cultures and the majority culture conducive to racial harmony?

- Is the purpose of using Maori vocabulary not to teach the Maori language in a coherent fashion, but to artificially insert Maori vocabulary into New Zealand English?

Some Background

There have been protests about the direction of New Zealand’s sex education programme at least since 2015, but to no avail. In 2015 a press release was issued by Family First New Zealand relating to concerns about the sex education programme in New Zealand schools. Concerns included:

- Reports in 2011 revealed that children as young as 12 are being taught about oral sex and told it’s acceptable to play with a girl’s private parts as long as “she’s okay with it”.

- 14-year-old girls were being taught how to put condoms on plastic penises,

- One female teacher imitated the noises she made during orgasm to her class of 15-year-olds.

- A mixed class of boys and girls were asked by the AIDS Foundation if they had masturbated lately and were given condoms and strawberry-flavoured lubricant.

- The same class were also given a leaflet featuring graphic pictures, terms including “co*k” and “wa*k”, and advice on the best condoms.

Reference was made to a 2013 Family Planning conference in 2013 – one of the sessions was Health Promotion and Sexuality Education with the specific topic of ‘Let’s start at the beginning! Sexuality Education for Year 1-4 students’. This piece of research has proved very hard to locate, but the recommendations of the paper have been adopted.

The plan to sexualise small children goes back to the 1940s, when the Rockefeller Foundation funded paedophile Alfred Kinsey.

‘In his 1948 book, “Sexual Behavior in the Human Male,” Kinsey naturally claimed proof that children are sexual from birth and unharmed by sex with adults. He even showed his “proof” on five tables timing the alleged “orgasms” from serial sexual abuse and rapes of children as young as 2 months old. (The babies and children screamed, fainted and/or convulsed during the abuse; Kinsey, an S&M bi-homosexual pedophile, called these reactions “orgasms.”)’ (‘Rockefeller’s Legacy Enabling Sexual Revolution’)

NZ Family Planning is affiliated to the the International Planned Parenthood Federation, which was founded by the Rockefeller Foundation. The Rockefeller Foundation also funds the Tavistock Institute, whose Gender Identity Development Service has been accused of fast-tracking children into changing gender.

The purpose of New Zealand’s sex education programme is to sexualise children, to damage them psychologically, to make them easier prey for child groomers and reduce their chances of building stable relationships and successful families in the future. It does not merely seek to create tolerance of transgenderism, but to actively direct children towards transgenderism.

It is clear that the intentions of the resource are destructive – just as we do not give a paedophile the benefit of the doubt when s/he is with children, we should not be giving Family Planning any lee-way. The Family Planning Clinic should play no role in our children’s upbringing.

See also:

30,000 Sign Petition to Stop New Zealander Schools Teaching Gender Diversity

Protect kids from Marxist sexualisation programs (original title):

‘Daniel Andrews’ Labor left government in Victoria [Australia] invokes neo-Marxist rhetoric to defend highly questionable school programs that encourage the sexualisation of children. […]

‘Like Safe Schools, the BRR program promotes a radical agenda divorced from its stated program objective. It promotes the sexualisation of children by inculcating techniques and beliefs centred on the premise that children are sexual. Instructors are encouraged to sexualise children, and children to sexualise themselves and their peers. They are asked to view highly sexualised personal ads and write their own, discuss transgenderism and anal sex. Program authors acknowledge that one exercise may cause “disassociation” in children.

‘Sexualising and inducing a dissociative state in children are methods of pedophilic predation. They are not methods of domestic violence prevention.’

The first three volumes of Navigating the Journey, years 1 to 6, are only available by purchase from Family Planning, but Years 7-8 is on-line.

Wow, nearly 3000 words with a punch. As I skim through it seems perfectly terrifying. Like waking from a nightmare that Joseph Goebbels had gained power over the civil service, to discover it was true.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think I agree with you Richard

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on uwerolandgross.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This info is completely disheartening for me …. there’s something sinister going on in our Kiwi schools

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Rangitikei Environmental Health Watch.

LikeLike

Sounds like grooming. In families where children are sexually abused they sometimes try out the same on other children. This “education” could be priming children to be abusers. Girls are often happy with their bodies until puberty and sexual abuse from men and boys start. Now they don’t have to wait until their teen years for the experience of being verbally and physically abused by their male peers. I expect the increase of abuse of girls resulting from this will be ignored.

LikeLike