The belief that Global Warming is an existential threat, requiring urgent action is the product of a dumbed-down education system. The belief that the world can painlessly transition away from fossil fuels is the product of an affluent and spoiled society. (@JWSpry)

The Zero Carbon Bill has just passed its third reading in parliament, in what Jacinda Ardern calls the ‘nuclear moment for this generation’. What she means, of course, is that Parliament is in effect nuking the New Zealand economy, and the New Zealand environment, on the back of what is frequently referred to as the greatest hoax in the history of science.

NZIER [NZ Institute of Economic Research] estimate the cost of Zero Carbon 2050 at $85b per year, about 28% of current GDP. This is economic suicide over New Zealand producing 1/588th of global man made greenhouse gases. It will be worse if the primary sector is ruined. (Steve Collins, Climate Chains: Follow The Science, Not Emotion)

Jacinda Ardern’s speech in support of the Bill can be found here. If one assumes that Ardern understands the subject matter of modern New Zealand’s ‘nuclear moment’, then one must also assume that any errors in her grandiose claims must made with full cognisance. And so we talking of deliberate falsehood rather than ‘mistakes’; these falsehoods include:

- The world is warming (ie unusually);

- The sea is rising (ie unusually);

- We are experiencing extreme weather events (ie to an unusual degree);

- New Zealand’s actions with regard to CO2 and methane will make a difference;

- The government is concerned about the environment;

- The government is concerned about food production.

‘The world is warming, undeniably it is warming’

If it were snowing at sea level in Rarotonga, politicians would be claiming that the world was burning up.

It is true that the world went through a warming between the mid 1970s and about 1998, but then there was a ‘pause’ in temperature increase. There was a pause in the pause, as it were, in the el Nino years of 2015-6, followed by the biggest temperature drop in recorded history in 2017 (see also Global Temperature Drops By 0.4 Degrees in Three Years). Satellite data, which dates from 1979, shows the increase in temperature in the 1980-1990s and then a levelling out (surface temperature data is meaningless due to the lack of gauges).

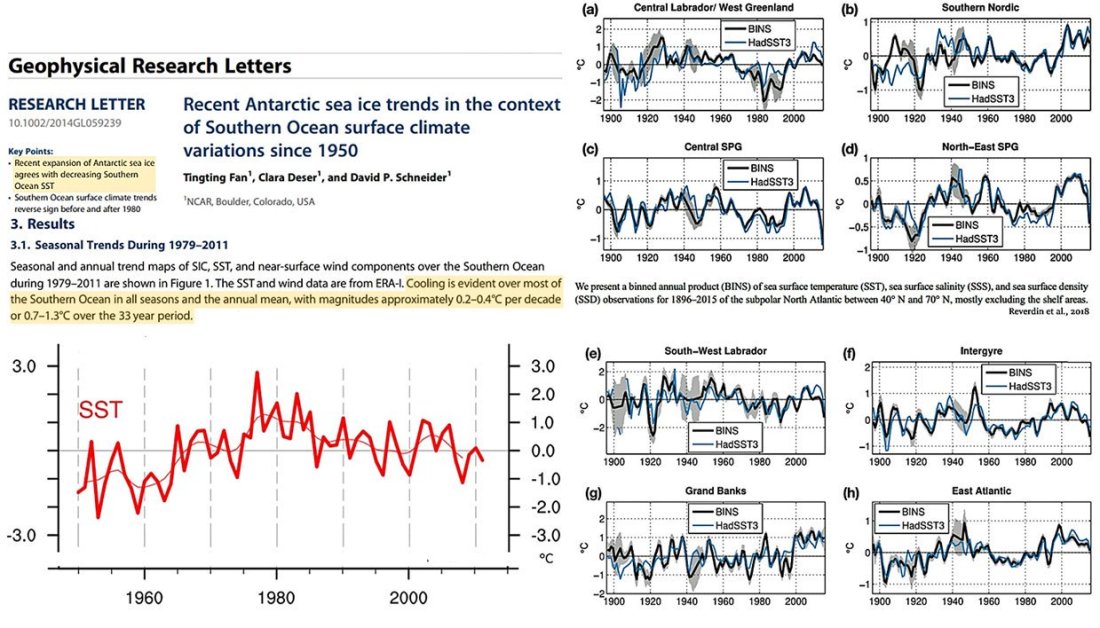

In 2014 (thus before the 2015-16 el Nino years) the extent of Antarctic sea ice was greater than it had been since 1979, An expedition to Antarctica in the summer of 2017-8 found that the Ross Ice Shelf is freezing rather than melting.

Abrupt changes such as plummeting temperatures and sudden deluges, as have been experienced in New Zealand in September or Greece in the height of the northern summer are consistent with the variability that is a feature of a cooling planet.

The principal weather change likely to accompany the cooling trend is

increased variability-alternating extremes of temperature and precipitation

in any given area-which would almost certainly lower average crop yields. (John H. Douglas, ‘Climate Change: Chilling Possibilities’, Science News Vol. 107

Thu, 25 Sep 1975, reproduced here )

The multiple reports of excessive snow and breaking of low temperature records in both the northern and southern hemispheres in October of this year might be put down to ‘weather’; they are however, consistent with the fact that Arctic and Antarctic sea ice is now at historic high levels. Antarctic sea ice expansion is consistent with the cooling trend that has been evident in the Southern ocean (data to 2011).

The magical 1.5 degrees

The 1.5 figure is one of those numbers that the IPCC plucks out of thin air, and backs up with no science whatsoever. The idea that an increase by 2 degrees in global temperature will cause widespread species extinction is bizarre given that many places in the world – mainland Greek villages for example – can experience within the space of a few months changes in temperature of forty degrees. If insects and birds find that the climate is gradually becoming too warm for their taste, they won’t suddenly drop dead, but it will show through a movement north or south. NO evidence has been provided that this is happening on a large and unusual scale.

‘Undeniably sea levels are rising’

The conviction that the sea is about to rise and engulf us all is widespread in New Zealand, thanks largely to propaganda from politicians and the media. The British tabloid, the Guardian, warned in 2017 that we are on course for a 3 degree increase in global temperature, and that this would result in major cities from Miami to The Hague to Osaka being engulfed. Given that weather forecast for Vostok Station, Antarctica, for Sunday evening of 10 November indicated temperatures of -48C, it seems unlikely that a three degree increase in temperature would result in the whole of Antarctica melting, leading to a massive inundation world-wide.

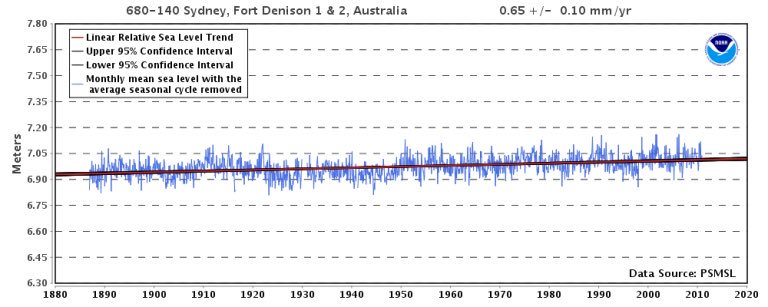

Global sea levels are been rising at pretty much the same level for hundreds of years – we are talking of an annual global sea rise of less than 2mm per annum. Some studies indicate that the rate of sea rise tapered off in the 1950s, see here and here. Frederiske et al., 2018 estimated that global sea levels rose at a rate of only 1.42 mm per year between 1958 and 2014. That figure closely coincides with the results of Dr. Simon Holgate from 2007: “The rate of sea level change was found to be larger in the early part of last century (2.03 ± 0.35 mm/yr 1904–1953), in comparison with the latter part (1.45 ± 0.34 mm/yr 1954–2003).”

The Wismar, Germany, record is one of the longest and most complete records of sea level rise in the world. It not only shows a long-term trend of 1.4 mm/year, but it shows no change in that trend (no acceleration over the past 50 years) since carbon dioxide levels have gone from 325 to 400 parts per million. Fort Denison in Sydney Harbour has been and remains one of the most reliable tide and sea gauging stations in the world, due to its position next to the largest body of water on earth, the Pacific Ocean. The sea level rise recorded at Fort Denison shows a steady trajectory.

An analysis of measurements from the world’s 225 best long-term coastal tide gauges indicated that the global average rate of sea-level change, is just under +1.5 mm/yr (about 6 inches per century), and it is not accelerating.

In the New Zealand context, members of the School of Surveying, Otago University and GNS NZ have analysed tide gauge records and vertical land movements for New Zealand, and found an average annual sea level rise of 0.9 mm over four main NZ centres, once subsidence is taken into account (this slide from their presentation at the International Surveyors (FIG) Conference in Helsinki 2017).

‘Some island nations will be impacted by rising sea levels.’ It is well known that in general islands in the Pacific are not experiencing threatening sea rise, and the island of Tuvalu for long the poster child for impending disaster, has in recent years actually gained in land mass. Back in 2012, sea rise expert Nils-Axel Mörner wrote:

In Tuvalu, the President continues to claim that they are in the process of being flooded. Yet, the tide-gauge data provide clear indication of a stability over the last 30 years.

A map published in National Geographic in 2016, showing where Earth has gained and lost land, revealed that Earth had gained more land than it had lost since 1985.

Along with other initiatives that involve spending money, ‘we are putting $300 million into international support to reduce climate change impacts, half of that going into the Pacific.’ Most New Zealanders do not begrudge money spent on projects aimed at raising the standard of living in the Pacific, such as education or clean water. However, money donated on a fraudulent basis, such as ‘rising sea levels’ when they are not actually rising, can only encourage corruption.

‘Undeniably we are experiencing extreme weather events’

Wellington’s last storm of any significance, the Wahine Storm, was in 1968. Even the last IPCC report failed to show an increase in extreme weather reports globally. Warren Buffet, insurance billionaire, said in 2014 that insurance companies do not factor in ‘climate change’ at all, having no expectation of major claims from an increase in hurricanes or other such catastrophes. Roger Pielke, until recently of Boulder University, Colorado, has found convincing evidence that climate change was not leading to higher rates of weather-related damages worldwide, once you correct for increasing population and wealth.

The role of Carbon Dioxide

The Zero Carbon Bill is premised on the assumptions that

- Trace elements such as CO2 especially, but also methane and even nitrous oxide, are important factors in global warming, outdignifying other factors, such as the sun;

- The anthropogenic component of atmospheric CO2 is significant;

- Initiatives from New Zealand will make a difference, actually and morally.

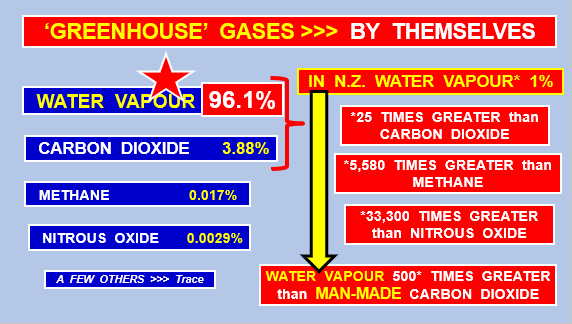

In his paper, How to Prove For Yourself That Carbon Dioxide Is NOT the Main Cause of Weather Changes and Climate Patterns (bundled here, p.11), New Zealander and professor emeritus of chemical engineering, Geoff Duffy, makes the following points:

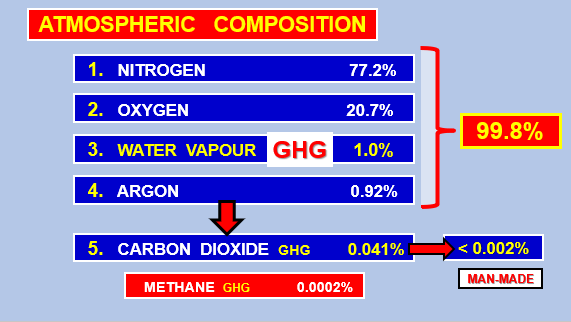

- CO2 is a poor greenhouse gas (absorber of radiation), completely swamped by water vapour and clouds.

- The concentration of carbon dioxide is so low that it is again dominated by water vapour.

- The only greenhouse gas of significance is water vapour, which unlike the other traces gases has the capacity to form clouds, precipitation and humidity.

These two graphs show the numerical insignificance of the trace ‘greenhouse gases:

(Slides provided by Geoffrey Duffy, DEng, PhD, BSc, ASTC Dip., FRSNZ, FIChemE, CEng, Professor Emeritus, Chemical Engineering, University of Auckland)

See also: Dr Ed Berry, Human CO2 Emissions Have Little Effect on Atmospheric CO2.

Methane (CH4) likewise is of no significance, as its absorbtion width falls completely within the absorbtion width of H2O.

CH4 is only 0.00017% (1.7 parts per million) of the atmosphere. Moreover, both of its bands occur at wavelengths where H2O is already absorbing substantially. Hence, any radiation that CH4 might absorb has already been absorbed by H2O. The ratio of the percentages of water to methane is such that the effects of CH4 are completely masked by H2O. The amount of CH4 must increase 100-fold to make it comparable to H2O. (Tom Sheahen, Methane the Irrelevant Greenhouse Gas)

Bud Bromley’s detailed account of the role of the different green house gases, CO2 is Not Causing Global Warming, reiterates the insignificance of methane as a greenhouse gas.

There is in fact evidence that CO2 has a cooling effect: see Carbon Dioxide is a Cooling Gas According to NASA, and Academia, Greenhouse Theory Refuted by 17 Papers Finding CO2 Can Make the Climate Colder.

The Sun is the Climate Knob and the Looming Threat is Glaciation

- The Sun is 4.6 billion years old.

- The Sun has surface area is 11,990 times that of the Earth’s. Its diameter is around 1,392,000 kilometres (865,000 miles), about 110 times wider than Earth’s.

- The mass of the Sun is approximately 330,000 times greater than that of Earth. You can fit 1.3 million earths into it.

- The Sun contains 99.86% of the mass in the Solar System.

- The Sun generates huge amounts of energy by combining hydrogen nuclei into helium. This process is called nuclear fusion.

- The Sun’s surface temperature is 5,500 °C.

- The Sun’s core is around 13600000 degrees Celsius.

- Light from the Sun reaches Earth in 8 minutes and 20 seconds. (Jamie Spry, The Sun: Climate Control Knob, Enemy of the Climate Cult)

‘I wish we had a climate like Germany’s’, is something no Greek has ever said. Cold kills far more people than heat. Because of the lack of sunspot activity, many scientists are predicting dangerous global cooling, a particularly frightening prospect if one lives in temperate/cool climates such as that ‘enjoyed’ in New Zealand. See: Scientists and Studies Predict Imminent Cooling and The Real Climate Crisis is Global Cooling and It May Already Have Started. A Mexican researcher is warning that his country should ‘beware the little ice age cycle’.

Dr Carlton Brown of Massey University has made an assessment of the dangers for New Zealanders presented by glaciation: Catastrophic Grand Solar Minimum Risks in the Years Ahead. A responsible government would be putting its efforts into ensuring that power is cheap and reliable, so that pensioners don’t die of cold, but there are no signs that this is a priority for the ’empathy government’.

‘We cannot afford to be a slow follower, for the environment’

The environmental claims made in support of the globalist climate narrative are perhaps the most obnoxious, the most fraudulent of the lot.

Ardern plans to replace the government’s fleet with EVs i.e. battery-driven vehicles. A recent German study indicates that when all factors are taken into consideration, evs emit more CO2 than diesel ones. But that is a minor point compared to the serious problems presented by battery driven power.

- Batteries are unsustainable: An essential component of lithium batteries is the rare earths, a limited resource – that’s why they’re called rare earths. [Correction: it has been pointed out that rare earths are in fact abundant on the earth’s surface, but that exploiting them is difficult, dangerous and, as mentioned below, causes environmental devastation.] To use them for every form of transport throughout the world is impossible – but there wasn’t a peep out of the government when the Wellington City Council did away with its trolley buses in favour of battery-powered buses.

- Rare earth mining is an environmentally devastating process.

- Battery disposal has serious environmental implications.

See e.g. James Taylor, Batteries Impose Hidden Environmental Costs for Wind and Solar Power.

See also: Child Miners Aged Four Living Hell on Earth .. Clearly the conditions faced by miners of rare earths are not the fault of cell-phone users, but given that the NZ government is confident that it can influence China and India to go zero carbon, it is sad that it has shown no interest in persuading other countries to ensure their wealth benefits even the smallest citizens.

Where will the energy coming from? Aside from hydro and thermal, already used in New Zealand, but which themselves have environmental implications, the favourite options for new energy sources are wind and solar. Huge solar and wind farms are being built in countries like China.

Both wind and solar have proved to be totally uneconomic, only existing gratis of subsidies, incentives and increased power prices to the consumer. The incentives feature prominently in the advertising of US solar companies, e.g. this one in Iowa.

Estimates of the useful life of wind turbines start from as little as 12 years, with both economic and environmental implications. The cost of decommissioning a wind turbine is somewhere between US$200,00 and $500,000. Whether useless wind turbines will be smartly decommissioned, rather than left to rot and pollute land and sea, is questionable.

That the visual environment has no value in today’s Green world is apparent from the sighting of a wind farm behind Scotland’s iconic Stirling castle.

But in any case, concerns over the blighting of the landscape have been overtaken by realisation of the destruction and the pollution represented by wind and solar.

Both wind and solar have huge footprints in relation to the power produced. This chart is from Strata, The Footprint of Energy: Land Use of U.S. Electricity Production, June 2017.

Analysis of a much touted proposal to make the US 100% renewable-reliant, showed that the necessary wind farms would cover twice the area of California. Often wind farms are at the expense of forest, e.g. Millions of Trees Have Been Chopped Down to Make Way for Scottish Wind Farms.

Wind farms present a risk to birds, bats, bugs and human beings

Wind farms are driving birds and bats to extinction – see also Wind Turbines Deadly to Bats, Costly to Farmers and Will Wind Turbines Ever Be Safe For Birds?

Maps depicting the USA’s best wind resource areas show that they are concentrated down the middle of the continent – right along migratory flyways for monarch butterflies, geese, endangered whooping cranes and other airborne species; along the Pacific Coast; and along the Atlantic Seaboard. (Paul Driessen, The Giga and Terra Scam of Offshore Wind Energy)

Wind farms are a enormous threat to human health. Negative effects of industrial wind turbines include: sleep disturbance, cognitive impairment, mental health and wellbeing, as well as cardiovascular disease, hearing impairment, tinnitus, and adverse birth outcomes.

New solar technologies also present a danger to bird life.

More sophisticated solar technologies include photovoltaic systems, trough systems with parabolic mirrors, and power towers as a focal point for solar flux. Studies (and local experience) show that they cause bird deaths through trauma or solar flux injury. See Kagan et al, Avian Mortality at Solar Energy Facilities in Southern California. The Ivanpah facility which uses a power tower, is said to kill 6,000 birds a year.

Both solar panels and wind turbines are full of toxic materials: disposing of both is problematic; in any case materials break up and disperse fragments in the wind.

‘Solar panels often contain lead, cadmium, and other toxic chemicals that cannot be removed without breaking apart the entire panel.’ (Michael Shellenberger)

A study by Environmental Waste found:

-

Solar panels create 300 times more toxic waste per unit of energy than do nuclear power plants.

-

If solar and nuclear produce the same amount of electricity over the next 25 years that nuclear produced in 2016, and the wastes are stacked on football fields, the nuclear waste would reach the height of the Leaning Tower of Pisa (52 meters), while the solar waste would reach the height of two Mt. Everests (16 km).

-

In countries like China, India, and Ghana, communities living near e-waste dumps often burn the waste in order to salvage the valuable copper wires for resale. Since this process requires burning off the plastic, the resulting smoke contains toxic fumes that are carcinogenic and teratogenic (birth defect-causing) when inhaled.

Because Germans are waking up to the threat posed by wind farms to birds, bats, and human health, new wind farm construction in Germany is grinding to a halt.

In Germany, real environmentalists are mounting a well-oiled revolt against the destruction of forests – the natural habitat of apex predators, like the endangered Red Kite. Environmentalists are also furious at the fact that Kites, Eagles and dozens of threatened bat species are being sliced and diced with impunity across Europe. Rural residents, driven mad in their homes or driven out of them by practically incessant turbine generated low-frequency noise and infrasound have taken their cases to law seeking injunctions and damages. (Wind Industry Crisis Spreads)

See also:

Solar Energy Badly Harms the Environment and Should be Taxed, Not Subsidised

Europe is Burning Our Forests for ‘Renewable Energy’. Wait, What?

One Billion (Pine) Trees

Not to be ignored is the cold-blooded decision to replant much (all?) of our agricultural land with pinus radiata forestry, which depletes the soil, is hostile to flora and fauna, and is ugly to boot.

‘We can not be a slow follower, for our food producers’

That protecting food producers is the last thing on the government’s agenda has been made crystal clear from the raft of measures taken to undermine the agricultural sector. Perhaps the most egregious of these is special provision for overseas concerns to purchase farmland, but only if they converted it to forestry. Consider, for example, the decision to allow a Japanese company to by-pass Overseas Investment regulations and buy 20,000 hectares of land to convert to forestry. – provided it is done in short order to allow the government to claim success for the One Billion Tree project.

The Zero Carbon Bill is in breach of the Paris Accord.

In a briefing sent 11 October to the Prime Minister’s Chief Science Adviser, Professor Juliet Gerrard, Environomics Trust CEO Peter Morgan pointed out that the terms of the Paris Climate Accord, which New Zealand has signed, forbid carbon mitigation policies that affect food production.

Article 2(1)(b) of the Paris Accord requires governments to:

‘..[increase] the ability to adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change and foster climate resilience and low greenhouse gas emissions development, in a manner that does not threaten food production.‘

Threatening the food production of New Zealand, a country that also exports food to other countries, is exactly what the Zero Carbon Bill is doing, along with the other measures taken by NZ government to undermine the agricultural sector.

Conclusion

Members of the public, including members of the New Zealand Climate Science Coalition, have made submissions on the Zero Carbon Bill, pointing out the complete lack of a scientific basis for it, and also the fact of the Bill being in breach of the Paris Accord. Any MP who claims to take an interest in the climate debate, including members of the Green Party, the associated select committee, and of course the Prime Minister, must be fully aware of the opposition to the bill and the weakness of the science.

For reasons one can only speculate on, Jacinda Ardern, and all members of parliament bar one, have chosen to ignore criticism of the science behind the climate narrative or questions regarding the implications if warming does in fact take place. They are ignoring the manifest economic and environmental consequences of the bill, and taken a step which unless reversed will cause unimaginable damage to the viability of New Zealand as a country.

See also:

Green Energy Future: a pictorial guide to the environmental catastrophe of renewables.

In Australia, Dr Bob Brown, former leader of the Australian Greens, was one of the first to break ranks when a wind farms was planned for the remote North-West of his home State, Tasmania: Hyper-Hypocrites: Greens Love Wind Power – In Your Backyard – But Never In Theirs

Peter Wadhams, Professor of Ocean Physics at Cambridge University, Next Year or the Year After the Arctic Will Be Free of Ice (August 2016)

Viv Forbes, Tomorrow’s Grim, Global, Green Dictatorship